from our newly launched handbook: MASTER BASIC DIGITAL TOOLS FOR RESEARCH available on any Amazon marketplace.

With Master ADVANCED Digital Tools for Research, to be released end of April 2025, both handbooks focus on conducting research projects using the most appropriate digital tools, techniques and resources, with smart information searching at the forefront.

Why? Because smart searching allows you:

• to stay in control of your information, rather than letting the tools dictate what you should see;

• to find the best data and information, even it is lost among millions of them;

• to identify information disorders, indispensable in our fake news age;

• to develop a critical and skeptical mindset toward the information you are exposed to;

• to ensure quality research results.

Our last post discussed tools; here are our takeaways on the best techniques.

Techniques in a nutshell

Searching for information with search engines begins well before the actual search, in other terms, it involves more than just finding information. In a nutshell:

- You identify the information you need as precisely as possible (basically, you must know what you need to find). It is the basis for all further actions.

- You craft the most efficient keywords, by identifying your topics’ key issues and/or key questions.

- You link these with appropriate commands, functions, and operators, to focus the search as precisely as possible.

- You press the Enter key and the search engine does the finding for you.

- You double-check the results, evaluate and assess them, and redo 2, 3, 4 and 5, until you are satisfied.

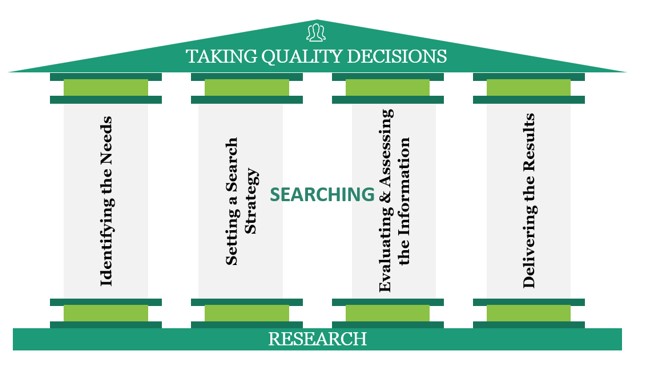

Finding valuable data and information for your research project is a multi-activity process, with two activities prior to the actual search, and two after. Prior ones involve identifying as precisely as possible the information needs, plus formulating a search strategy and plan. The real search can then start on solid foundations. Then, it cannot be completed without a proper assessment and evaluation of the collected information. There is then the delivery of the results. These activities are the indispensable pillars of any quality decision-taking process.

To put it another way, you should not jump into your favorite search engine headfirst. Rather, take time to elicit your needs and determine the best course of action for your research project. Act upstream (i.e., before searching), to save time and efforts downstream (i.e., while seeking, processing, evaluating, and delivering information). Think before you search. It takes time but it pays off in the long run. It limits frustration later. Many amazing digital tools to find information now exist; researchers should understand their pros, cons and limits and use a diversity of them, methodically and critically to achieve quality results.

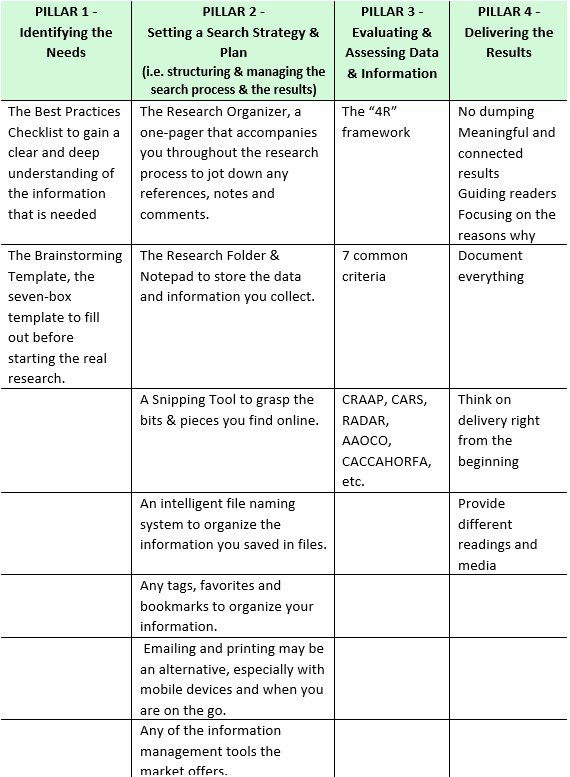

In a nutshell, here are the different resources we propose to support each pillar.

In more detail:s

PILLAR 1 – Identifying the Needs

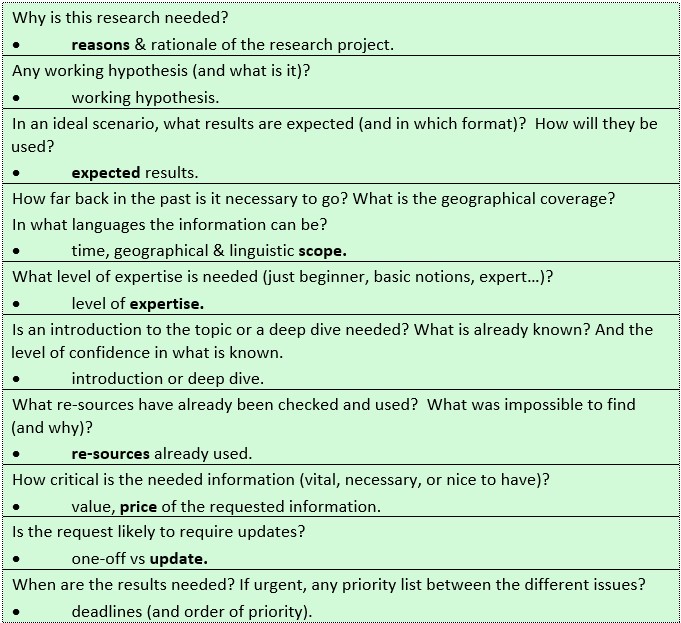

The “Best Practices Checklist” allows you to investigate different aspects behind your research project and to set some solid foundation. It consists in ten questions that you can ask yourself or your audience. Done thoroughly, you have a clear and deep understanding of the information that is required. Note that not all questions apply to every request. Consider their respective context and depth when utilizing them.

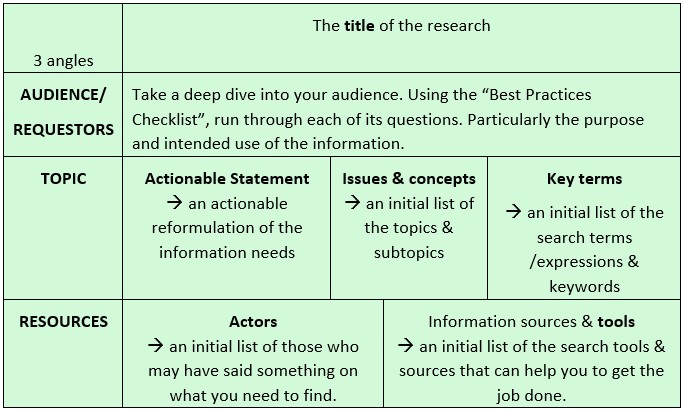

The “Brainstorming Template” examines your research project from three perspectives: audience, topic and resources. Like the “Best Practices Checklist”, it helps to take into account all aspects of your research project.

PILLAR 2 – Setting a Search Strategy & Plan

(i.e. structuring & managing the search process & results)

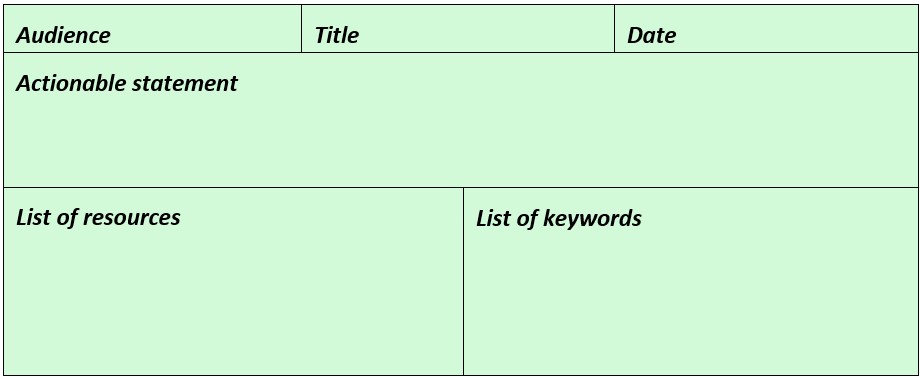

The “Research Organizer” is a one-pager which states your intended audience, research title, start date and your actionable statement. The rest of the page is divided into 2 columns, one with the list of resources to check, the other with the keywords to use.

This one-pager is especially useful to get you started but it can accompany you throughout your research process. Always in front of you, it is a reminder of what you need to do: the objectives of the research with the “Actionable Statement” and then, your resources and keywords, which you update as you progress. It allows you to develop and follow a strategy, to prioritize and be better organized. Consider it as a compass. This operational document is where you take notes and keep track of what you do, have done and still need to do. It is yours; it may be quite messy at the end of your project; you will not hand it over.

The “Research Folder” and the “Notepad”. This is where you store the information you collect; the first for electronic files, the second for bits and pieces, and for references and links.

Beside:

A screen capture tool is very useful to capture bits and pieces of any webpages without having to worry about formatting and code issues. Some of them are: Windows Snipping Tool, Snagit, Screenrec, etc.

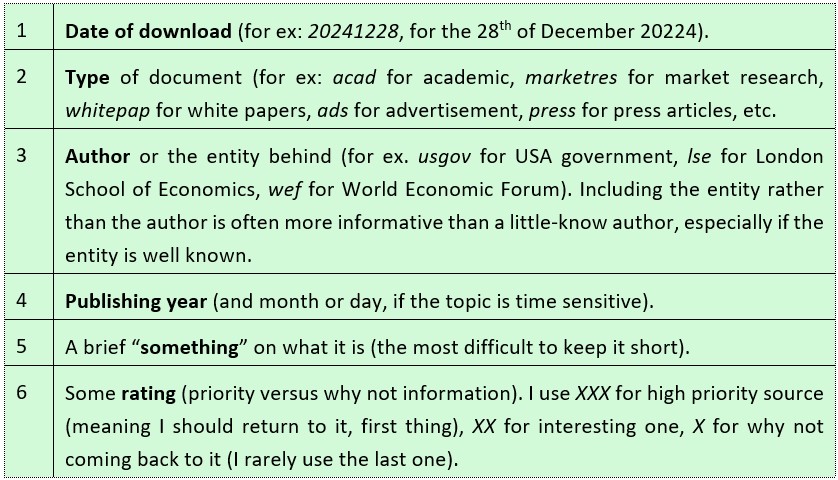

By adopting a smart system to name your files, you ensure finding your information more easily, thus an intelligent file naming system. Well crafted, you can instantly determine what each file contains without having to open it. Though it may take some time to set up, it saves a great deal of time long-term. The following items can be included in your file names:

210601_ACAD_LSE_1501_fakenewssearch_xxx.pdf : here is an example of a meaningful file name.

The above are just suggestions. Use some that make sense to you and which are related to your context and research. Also, try to make them short (using your own abbreviations) as long file names may become difficult to handle. Avoid changing them over time. Technically (it is a computer limit), they should not exceed 250 characters (taking into account that the 250 characters include the path on where the file is stored on your computer, on a network or on the cloud). The challenge is to keep them short, nevertheless informative. Find what is right for you. Intelligent file naming is complementary to the file search function of most file explorers.

Some tags, favorites, and bookmarks systems can also help you to organize and keep track of your information. However, if used without a plan and too generously, it can become confusing and useless. Think carefully before utilizing them extensively, otherwise, their purpose is killed.

You may find emailing and printing useful from time to time. The first, especially when you are away from your desktop and do not use the cloud. You can email yourself the great information or link you just found on your mobile devices for example, which you can then integrate when you are back at your computer. Nevertheless, in our mobile world, more and more systems allow working seamlessly across devices. As to printing, even if it is sometimes helpful to see something on paper, think about saving the planet before printing extensively. Reading on paper is nevertheless a very personal thing, which depends on one’s preferences, the type of research, results, and delivery channels.

To keep track of your sources, a detailed “Source Checklist” can be interesting for in-depth searches, and/or for research lasting over a long period, and/or involving various researchers. It proposes several descriptors that can be included, such as the dates of the information & of your visit (when); where the information was found and how; what it is about; why it is relevant; any relevance rating; any comments; and any suggestions of further sources. Keep in mind the WWWWWH framework (for Who-When-Where-Why-What-How) to help you define your information exhaustively.

Finally, some market-based information management tools may fit into your researcher’s suitcase. Many help to manage various aspects of a research process, especially the organization of information. Note that some take time to onboard before they are fully operational. Research projects lasting a long time, which are complex (such as doctoral dissertations), and those that involve multiple researchers may benefit from them. Try to onboard them early enough in the research process. Here is a selection of them:

- “reference management” tools (such as, EndNote, Zotero and Mendeley),

- “writing” tools (such as Scrivener),

- “notes taking” tools (such as Evernote and OneNote),

- “hybrid” tools (such as Notion, OmniOutliner, ClickUp and Mind Mapping),

- AI-based tools.

Various tools based on artificial intelligence can assist researchers in many ways. Still in their infancy their developments should be monitored carefully.

PILLAR 3 – Evaluating & Assessing Data & Information

Managing the research process (and the results thereof) is essential, as are evaluating and assessing the data and information you plan to use. Since ancient times, people have attempted to separate quality information from lousy one. Some long-established systems (such as the peer review process for scientific papers) have shown some limits during the first months of the COVID-19 epidemy; the Lancet and The New England Journal of Medicine, two prestigious scientific publications, got fooled in 2020 by “unreliable” and not sufficiently backed-up information on COVID-19. Consequently, and also because of the explosion of information disorders, smart researchers need to learn how to assess and evaluate data and information. We reviewed various systems (CRAAP, CARS, RADAR, AAOCO, CACCAHORFA, etc.) and extracted 7 commonalities:

- “time” (timeliness, agenda, check the date, currency, date, recency)

- “author” (authority, credentials, ask the experts)

- “reliability” (purpose, credibility, reason for writing)

- “accuracy”

- “coverage” (content, scope, scope of coverage)

- “point of view” (objectivity, fairness, reasonableness

- “relevance”

- “coverage” (content, scope, scope of coverage).

We proposed a simple framework which incorporates most of these criteria. It is the “4R”, for “Recent”, “Relevant”, “Reliable” and “Rich” information. In other terms:

- Recency In relation to my topic, my results are up-to-date, timely and current

- Relevancy They answer my research questions or I justify why they do not

- Reliability They are trustworthy and reliable. I trust their authors, their intentions, their expertise and author-ity.

- Richness I provide a variety of contextualized perspectives and points of view.

PILLAR 4 – Delivering the Results

After carefully identifying the information needs, then searching for the best data and information, systematically managing the overall process, and assessing everything, delivering your results needs deserves your special attention; it can make or break your research project. What is the use of all your smart research if your results are poorly presented. Our handbooks do not cover this in detail, as many exist on the market. Nevertheless, here are our tips as delivering results is concerned.

Generally speaking, don’t dump a collection of disconnected information and documents. Think about how your results will be used. Guide your audience into your results. Remember, your audience is not in your head and has not gone through the search process. Don’t assume it understands the reasons why you are providing this or that information. Being overtly explicit is rarely an issue. Give it the reasons why: justify your selection. Contextualize, connect and source everything to give it meaning. In other terms, make your results meaningful. This should be your leitmotiv all along your research. You and your audience will be able to make informed decisions, based on meaningful, relevant, and reliable information.

Along this line, document the different information and statements you make, whatever your delivery method. This continues to be a standard of quality research.

Consider how you deliver your results, already at the beginning of your research project. Doing this can give some precious guidelines for the whole research. For example, being clear on how the results are to be used can guide the search in a specific direction. Knowing about who (young vs old, expert vs novices, man, woman, etc.) will use these results can allow to target sources specifically for such audience. Generally, asking your audience, the type and form of results it expects to get in an ideal scenario can help to search in a more relevant way. Even if it may not have thought about this aspect, raising this issue will usually make it talk, giving you precious hints on what and how you need to investigate your issues.

Mid 2020s, less and less people like to read dozens of textual pages. Don’t hesitate to provide different readings and levels: the essence (abstract type) then one or two levels of details. See your delivery in 3D, or in a hypertext way. Include visuals, especially if your audience belong to the new generations.

Our second handbook (Master ADVANCED Digital Tools for Research) discusses advanced search tools and techniques: various alternatives to Google, some deep web resources, some professional information systems, and some recent information channels, such as social media and multimedia. We see as well various competitive intelligence techniques, as they can greatly empower any researchers. Our Smart Researcher’s 10 Golden Rules conclude our handbook.